“The very least you can do in your life is to figure out what you hope for. The most you can do is live inside that hope, running down its hallways, touching the walls on both sides.” — Barbara Kingsolver, from Animal Dreams

In 1982 I spent a memorable Easter week with Salvadorians in a refugee camp. These gentle people, mostly peasant farmers, had fled the violence of the war to the camps in Honduras. The night before I left I sat with a small group under a starry sky while one after another they told their stories.

One farmer told me that the Salvadoran military (with Reagan administration support, my tax dollar, by the way) had been bombing homes and killing people in his area. His family and neighbors sought shelter in the church, but the military sought them there, as well. So they left for the mountains, without food or much clothing, walking at night with children, the elderly and pregnant women

One day as they journeyed, they sent his sister into a town for some corn. She was chosen because she was retarded and unlikely to be questioned by the authorities. Her five-year-old boy went with her. Unfortunately, she was spotted by soldiers who then began to interrogate her. When she said nothing, they threatened her by placing a grenade in her mouth. She still didn’t talk, so they removed the grenade, raped her, tied her to a tree and cut her to pieces with a machete. The boy later found the rest of the group and told them what he had seen happen to his mother. After a long trip they finally crossed over the Honduran border.

As we sat in a circle that spring night, each refugee shared a similar story. Each had lost family members and friends to the civil war. The evening was punctuated with tears and, occasional bursts of laughter.

What struck me in the midst of this tragedy was their growing spiritual renewal. In this trapped place, these refugees were learning to read for the first time. They were learning new skills such as shoemaking and health care. But most important, they were learning the power of community. In this camp “basic Christian communities,” born out of liberation theology, were flourishing. When the refugees met to deal with daily issues and plan work schedules, they began with Bible reading, reflection and prayer. For the first time, many were attending school and learning the value of education. They were becoming empowered in new ways.

The man who had lost his sister told me, “We have a living faith and instead of diminishing, it increases every day that passes by.”

Are you optimistic or pessimistic?

Albert Schweitzer said, “However much concerned I was at the problem of misery in the world, I never let myself get lost in broodings over it; I always held firmly to the thought that each of us can do a little to bring some portion of it to an end.”

Albert Schweitzer said, “However much concerned I was at the problem of misery in the world, I never let myself get lost in broodings over it; I always held firmly to the thought that each of us can do a little to bring some portion of it to an end.”

Should we despair or be hopeful? For years, I’ve paid attention to how people talk about their personal struggles between pessimism and optimism. Two of these, Bill Moyers and Paul Hawken, shared their thoughts with new graduates. Here’s Bill Moyers addressing graduates at Hamilton College in 2006:

“I find I am alternatively afraid, cantankerous, bewildered, often hostile, sometimes gracious, and battered by a hundred new sensations every day. I can be filled with pessimism as gloomy as the depth of the middle ages, yet deep within me I’m possessed of a hope that simply won’t quit. A friend on Wall Street said one day that he was optimistic about the market, and I asked him, “Then why do you look so worried?” He replied, “Because I’m not sure my optimism is justified.” Neither am I. So I vacillate between the determination to act, to change things, and the desire to retreat into the snuggeries of self, family, and friends.

And Paul Hawken’s commencement address, University of Portland, 2009:

Forget that this task of planet-saving is not possible in the time required. Don’t be put off by people who know what is not possible. Do what needs to be done, and check to see if it was impossible only after you are done.

When asked if I am pessimistic or optimistic about the future, my answer is always the same: If you look at the science about what is happening on earth and aren’t pessimistic, you don’t understand data. But if you meet the people who are working to restore this earth and the lives of the poor, and you aren’t optimistic, you haven’t got a pulse.

Should we be hopeful about voting?

As I write this in Arkansas, we are fighting against yet one more mean state law. This one, like one just passed in Indiana, would let business owners, based on their religion, refuse to serve anyone they choose. The bill has passed both legislative houses and awaits the governor’s signature. If signed, discrimination and bigotry—disguised in the cloak of “religious freedom”—will once again be legal.

As I write this in Arkansas, we are fighting against yet one more mean state law. This one, like one just passed in Indiana, would let business owners, based on their religion, refuse to serve anyone they choose. The bill has passed both legislative houses and awaits the governor’s signature. If signed, discrimination and bigotry—disguised in the cloak of “religious freedom”—will once again be legal.

The cynical gerrymandering of districts in recent decades is making it almost impossible for each person to have an equal say. And since 2013 when the Supreme Court basically struck down the 1965 Voting Rights Act, we’ve watched state after state even further erode targeted people’s ability to vote and determine their futures.

I once sat on a bus next to a man who described himself as normally optimistic, but who was despondent about the results of a recent election. Seventy-five percent of the people in his state of Texas had voted down something dear to his heart. How could people vote that way, he wondered? Where was our spiritual center? Were we never to progress as a society?

I’m not convinced we haven’t moved forward. Had that election been held 100 years ago, only white males would have voted. Had it been held 50 years ago, it’s likely that while white women would have been in the voting booths, few African Americans would have cast any ballots. So like Moyers and Hawken, I find myself torn. Even if I’m not happy about the results of recent events, at least we’ve made progress, however flawed. But I’m weary of the real threat to that progress.

I’ve felt all these emotions at once

Fifty years ago this month state troopers fractured the skull of John Lewis as he led a march across the bridge in Selma, Alabama, to help secure those voting rights for African Americans. He was also the youngest speaker at the March on Washington. Reflecting in his autobiography on the hopefulness in the speech that day by Martin Luther King, Lewis said,

Fifty years ago this month state troopers fractured the skull of John Lewis as he led a march across the bridge in Selma, Alabama, to help secure those voting rights for African Americans. He was also the youngest speaker at the March on Washington. Reflecting in his autobiography on the hopefulness in the speech that day by Martin Luther King, Lewis said,

As for Dr. King’s speech, I was not disturbed at all by its message of hope and harmony. I have always believed there is room for both outrage and anger and optimism and love. Many, many times in my life, in many situations and circumstances, I have felt all these emotions at once. I think this is something that separated me from many of my colleagues in SNCC—the fact that they saw this struggle as an either/or situation, that they believed it was impossible to feel hope and love at the same time as you felt anger and a sense of injustice.

A moment of double vision

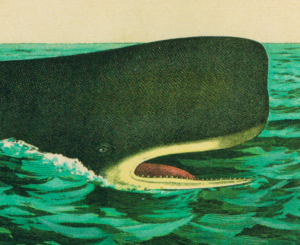

A fitting image for our time may well be the whale with its small eyes pointed outward from opposite sides of its huge head. Essayist Loren Eiseley pondered if, given this arrangement, the whale can coordinate the meaning of two sights at once. If not, the creature must experience two separate worlds at once.

A fitting image for our time may well be the whale with its small eyes pointed outward from opposite sides of its huge head. Essayist Loren Eiseley pondered if, given this arrangement, the whale can coordinate the meaning of two sights at once. If not, the creature must experience two separate worlds at once.

He tells of one whale harpooned in the icy ocean in the South Pacific and wonders what it saw as it was being tugged toward the ship?

With one dimming affectionate eye, [it saw] the ancient mother, the heaving expanse of the universal sea. With the other it glimpsed with indescribable foreboding the approaching shape of man, the messenger of death and change. So it was the dying whale in its dissociated vision had arrived, if momentarily, at the one true place where the nature of the past mingles with the onrush of the future…. It is an instant to remember, for it will come, in turn, to man.

That instant of double vision seems to have arrived for us. With one eye, we see ourselves wrenched toward a grim future of shifting climate, depleted soil, forests turned desert, and an inability to grow enough food. We see wars with no clear sides, terrorism, racism, economic injustice, to name just a few. We are anxious, overwhelmed, angry, hopeless. With the other eye we nostalgically see an ancient Earth brimming with forests and wildlife, plenty of rich soil for farming. We see the world as it should be—with peace, economic justice, dignity and equality. We see a hopeful path forward, even if it is long and arduous.

I wish this had been a happier piece. I consider myself somewhat hopeful. But hope is work. Like muscles, hope has to exercise regularly and over time to be any good. King said, “The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” We have to struggle with the issues of today but hope for the better tomorrow. As Barbara Kingsolver suggests, let’s figure out what we hope for and then “live inside that hope, running down its hallways, touching the walls on both sides.”

Painting by Rufino Tamayo, Man and the Infinite, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium. Selma photo: FBI, really! : )

No comments yet.