Journalist and social activist Dorothy Day, along with Peter Maurin, started the newspaper The Catholic Worker in 1933. It sold it for a penny a copy, which still the price. With writers such as Thomas Merton and Daniel Berrigan the paper connected the church’s teachings with social justice issues, as it still does today. At the same time, Day and Maurin also began the Catholic Worker movement. From the first house in New York City this movement has grown to more than 200 communities around the world, and the people who live in them work daily to bring about social justice in a variety of ways. Dorothy Day, who lived from 1897 to 1980, is now being considered for sainthood by the Catholic Church.

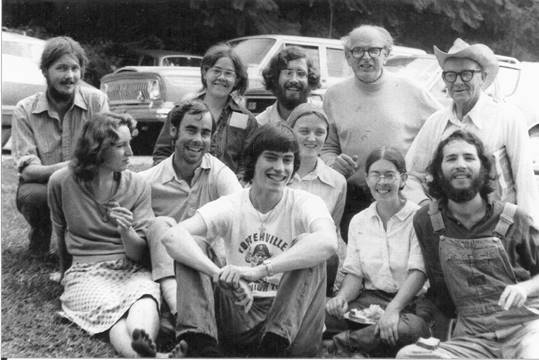

Peggy Scherer (front row, second from right) was part of this movement, working closely with Day and seeing it from a variety of angles. I got to know Peggy when we worked together at Heifer International. Here are her thoughts on living in that community.

Tell us about living in the Catholic Worker community.

I lived in three different Catholic Worker Houses between 1974 and 1986, all part of the New York City Catholic Worker. Each had a different purpose, size, and character. Tivoli, a 70–some-acre property overlooking the Hudson, was originally bought to house conferences during the Vietnam war period, as well as to grow some food for the city and a place to offer hospitality. During my time there were 40 to 100 people staying there. Tivoli was sold four years after I arrived and was replaced by Marlboro, which was meant to house some aging Catholic Workers, grow food, and provide a respite for Catholic Worker folks from NYC.

I lived in three different Catholic Worker Houses between 1974 and 1986, all part of the New York City Catholic Worker. Each had a different purpose, size, and character. Tivoli, a 70–some-acre property overlooking the Hudson, was originally bought to house conferences during the Vietnam war period, as well as to grow some food for the city and a place to offer hospitality. During my time there were 40 to 100 people staying there. Tivoli was sold four years after I arrived and was replaced by Marlboro, which was meant to house some aging Catholic Workers, grow food, and provide a respite for Catholic Worker folks from NYC.

And I lived at St. Joseph House, one of two city locations, which provided hospitality and offered a soup meal to up to several hundred a day. And one floor held a workroom where The Catholic Worker paper was prepared for mailing. During my years that meant folding and labeling nearly 100,000 papers nine times each year; this was full-time work for some, and many pitched in when they could.

What was it like to live and work in community?

Each place was different, though there were similarities. The Catholic Worker was a group that of offered food, shelter and clothing to those in need, and stood up for a more just world and against those forces that led to injustice. The mainstay of the vision and the work and the daily life was practicing the “Works of Mercy” in the Christian tradition. One way to look at this was we helped those in need, and also asked why they were in need by revealing and challenging injustice.

Community formed around the work, so it was secondary to the work, unlike many other “communities.” Each place had a small number of volunteers (we called them “responsible people”) who ran the houses, answered the door to help folks who came; wrote, edited and mailed the paper; participated in protests; and dealt with the needs of those offered hospitality. Each place had a small, long-term group, with many others coming and going, so the atmosphere changed somewhat as folks with different personalities came and went. The line between those who “were in need” and those who weren’t was not always clear, and people of all ages and backgrounds were in each. Some had a strong sense of faith, mainly the Catholic tradition, though many were not Catholic but quite welcome. In all, one way or another there was a constant “dialogue” in words and actions between faith and its practice. A handful of us prayed together daily and Mass was celebrated regularly in each place.

There were celebrations, tensions and always things going on. Lots of work and lots of people. It was stimulating, educational, thought provoking, fun, exasperating. There were happy times and sad ones, due to the challenges and hardships—physical and mental—which various folks suffered.

During her life, Dorothy always had the final word on what was done and where the various properties were (she sold and bought different ones in the city and the country several times). Often there were folks from various countries in each of the “houses,” which is how we referred to the various locations, including the dozens of independent Catholic Worker houses around the country and the world. And in each house, there was always a handful of people who really were the decision makers, though that was rarely acknowledged (and often denied).

What were the downsides?

The downsides, or what felt like downsides, varied. The work could be exhausting, as could the constant comings and goings of people. The wide variety of people could be exasperating as well as enjoyable and fascinating. The “chain of command” was not real clear, and while we usually tried to get broad agreement, there were times when decisions were made by some that were not well received by others.

We lived in voluntary poverty, which rarely seemed a problem since we got food, shelter, clothes from donations, $10 a week spending money, and special needs—a trip to an ill family member, or to the dentist—were provided for. But over time most of us wanted to have our own space and a little less excitement. Many left to pursue a dream, a different kind of work, to return to school, and so on.

Did living in this community stretch you or help you grow?

It helped us grow by exposing us to many new and different people and situations and challenges an ideas, visions, and information. The conversations were ongoing and engaging. Some were structured like the “Friday night meetings,” a sort of a speaker’s series where all kinds of people spoke about a topic or experience, and then each day provided much food for thought and for conversation. We all learned from this constant mix of theory and reality. What is nonviolence, for example, according to Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and so on. Then what does that mean when you need to break up a fight on the soup line or in arguments about who’s using all the hot water? Or how do you really help someone having a psychotic break? Or a manic episode? Our discussions and articles in the newspaper were enlightened and tempered by the back and forth.

It was also a place to make life-long friends, and to feel part of something important. And, it helped many of us see more clearly what we wanted to pursue next.

What advice would you give to someone who wanted to be part of a community like this?

I’d encourage anyone thinking of joining a Catholic Worker community, or another service community, to look around—there are many options, in location, focus, people. Find one that seems to fit, but stretch yourself too. Do something new that will challenge, educate and inspire you. Many experiences will show you the flaws in various systems and help you find how to address those injustices. None of us can understand poverty, racism, and other ills of our society and world as well as we could if we lived among those suffering because of them. Break bread with folks. And think about how no group of “victims of injustice” is only that: they too have dreams and information, ideas and contributions, and often can analyze situations far better than we can, and teach us a lot.

You may perhaps join a community to “help others” but inevitably you’ll receive more than you will give. Dorothy Day was a wise woman; one of her quotes comes to mind: “What we would like to do is change the world—make it a little simpler for people to feed, clothe, and shelter themselves as God intended for them to do.” I am thankful that the experience of doing this also led to my finding others who shared the same vision, and shared a part of their lives in a community of service.

[…] science research station—as members eat, live and work alongside each other. In others, like the Catholic Worker, volunteers live together to work on a cause. They can form around a neighborhood association or […]