Let’s commit to oblivion these symbols & what they stand for

By Tom Peterson

Last week riding with some friends in North Carolina we passed a Confederate flag proudly flying along the highway. It was a jarring reminder that Jim Crow is alive and well. But it wasn’t surprising. After all, I do live in Arkansas. And we all can hear an occasional talking head on mainstream media pretending that the Civil War was not about slavery and treason but about state’s rights and other made-up causes. It’s still nothing short of mind boggling that racism and its symbols are thriving.

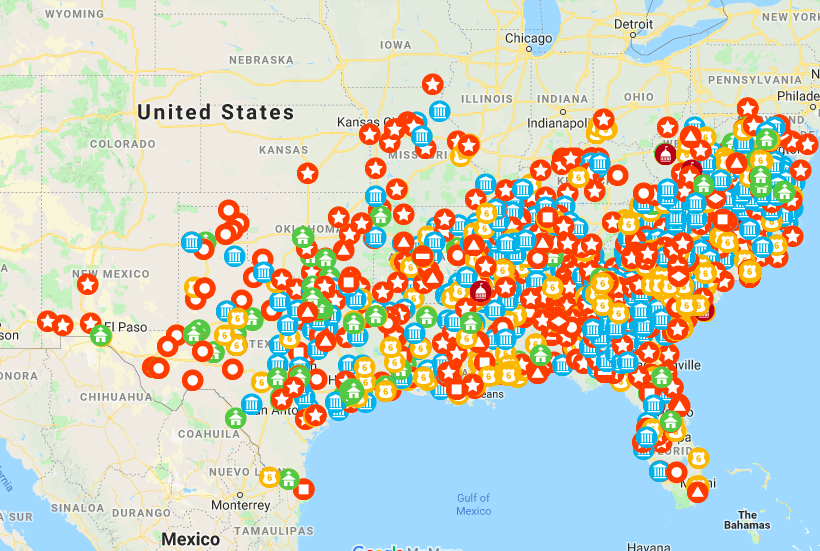

Many public symbols of the Confederacy are still with us, as well. The Southern Poverty Law Center, or SPLC, has mapped 1,740 of them scattered across the nation but mostly  in the South. These take the form of monuments, place names (such as streets, cities, counties), schools, and more. Did you know that the most popular street name in Virginia is “Lee,” after the Confederate general? Most of these symbols appeared during two periods: from the 1890s through the 1920s and in the years following the 1954 Brown-vs.-Board of Education Supreme Court decision and Little Rock’s Central High School desegregation in 1957. They were and are racist assertions, warnings to not resist white dominance.

in the South. These take the form of monuments, place names (such as streets, cities, counties), schools, and more. Did you know that the most popular street name in Virginia is “Lee,” after the Confederate general? Most of these symbols appeared during two periods: from the 1890s through the 1920s and in the years following the 1954 Brown-vs.-Board of Education Supreme Court decision and Little Rock’s Central High School desegregation in 1957. They were and are racist assertions, warnings to not resist white dominance.

In 1961 the Confederate flag was raised in front of the South Carolina state house for the first time in a century. It was, said Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson, “a middle finger directed at the federal government. It was flown there as a symbol of massive resistance to racial desegregation. Period.” This flag and the thousands of others found on bumper stickers and t-shirts have one purpose: reinforce white supremacy.

But activists are steadily taking them on, one at a time. “All the world’s a stage,” said William Shakespeare, and an act can also be a powerful symbol in this real-world theatre. In June 2015 in an act of civil disobedience Bree Newsome climbed up that flagpole in South Carolina and brought this particular flag down. “We removed the flag today because we can’t wait any longer. We can’t continue like this another day,” she said. “It’s time for a new chapter where we are sincere about dismantling white supremacy and building toward true racial justice and equality.”

But activists are steadily taking them on, one at a time. “All the world’s a stage,” said William Shakespeare, and an act can also be a powerful symbol in this real-world theatre. In June 2015 in an act of civil disobedience Bree Newsome climbed up that flagpole in South Carolina and brought this particular flag down. “We removed the flag today because we can’t wait any longer. We can’t continue like this another day,” she said. “It’s time for a new chapter where we are sincere about dismantling white supremacy and building toward true racial justice and equality.”

Connect the dots

Symbols and acts of violence often go hand in hand. In 2015, a young man entered an African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and murdered nine members, telling his victims “You rape our women and you’re taking over our country and you have to go.” Among the many racist symbols found on his website was, not surprisingly, the Confederate battle flag. It’s not hard to connect the dots.

The SPLC reports that since that Charleston church shooting more than 100 of these symbols have come down. A few years ago in my own town of Little Rock, Confederate Boulevard was renamed Springer Avenue after a historically prominent African American family. But three monuments to Confederates still stand on the Arkansas capitol grounds just blocks from my house.

Ironically, one person who wouldn’t have been happy about the proliferation of Confederate symbols was Robert E. Lee himself. It turns out he opposed erecting confederate monuments. “I think it wiser not to keep open the sores of war,” said Lee, “but to follow the example of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, and to commit to oblivion the feelings it engendered.”

Symbols of racism should never be welcome in our public spaces and need to be, as Lee urged, committed to oblivion.

Photo of Bree Newsome by Grant Baldwin, Flickr

No comments yet.