By Tom Peterson

Although we’re rarely conscious of it we use maps all the time. Every day we use mental maps to navigate the rooms of our home, get to school and work. Maps teach us as children about our strange and wonderful world—green is vegetation, tan is desert, bumps are mountains. And we learn to recognize the location and shape of Australia. As we grow older maps evoke deeper meanings: a simple line drawn across an east Asian peninsula represents the vast chasm between the daily lives of North and South Koreans.

Now we map everything imaginable, from Mars to DNA. And services like Google Maps use satellites and GIS to show and tell us the best way — even avoiding heavy traffic — to find a nearby taco.

What is a mind map?

What is a mind map?

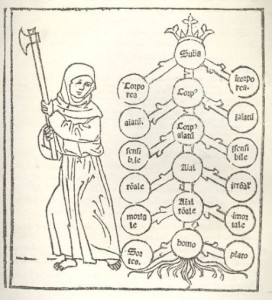

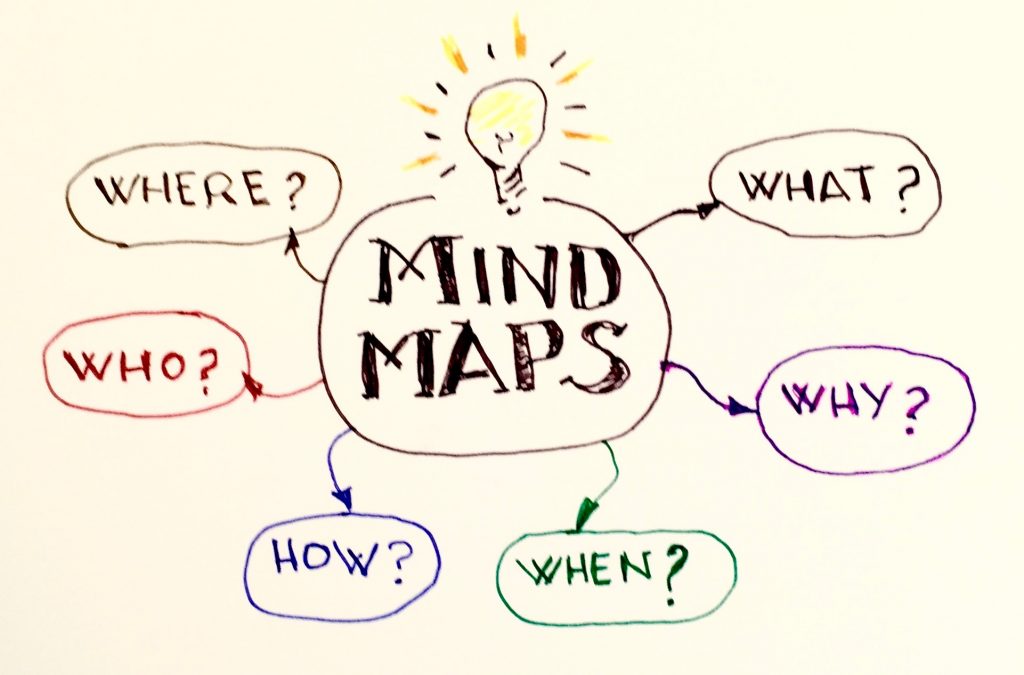

Like their geographical and scientific counterparts, mind maps can help you visually outline and make sense of all kinds of complex issues and connections using both left and right brains. Tony Buzan coined the phrase “mind map” and popularized their use in the 1970s but they’ve been around since at least the third century when Porphyry of Tyre mapped out Aristotle’s categories (left). Walt Disney used one in 1957 to map out his various enterprises.

Why use mind maps?

Because they are at the same time hierarchical and non-linear, mind maps help us organize our thoughts in new ways. They help us see how things are structured and connected, making them excellent tools for strategic planning—for example, SWOT (Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, Threat) analysis—or asset mapping. A mind map can help you see all at once the many aspects of a new project you’re about to start, possibly leading you to new ideas and approaches. Many teachers have their students use mind maps as organizing tools to plan out their essays.

Because they are at the same time hierarchical and non-linear, mind maps help us organize our thoughts in new ways. They help us see how things are structured and connected, making them excellent tools for strategic planning—for example, SWOT (Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, Threat) analysis—or asset mapping. A mind map can help you see all at once the many aspects of a new project you’re about to start, possibly leading you to new ideas and approaches. Many teachers have their students use mind maps as organizing tools to plan out their essays.

Mind maps work at any level so you can pick your altitude. Go up to 35,000 feet to struggle with a complex social issue in your community or zoom in close to map out your personal goals for the coming year. Because you can see where your energy is focused, what influences what, which assets connect to which challenges, mind maps foster creativity and often reveal innovative solutions that might have otherwise been missed.

Who & Where?

You could stop reading and make a mind map on a scrap of paper right now. If you journal you could map  your way through an issue you’re struggling with. You could sit at a table with any subject expert and jointly create a mind map about their work or field. When I’m working on my own or with one other person a large whiteboard is great, but sheets of 11×17 paper work as well. Use what you’ve got; an artist friend, Betty LaDuke, and I sat in a New York City café late one night and drew out on a napkin the various elements of a giant art project (and over the next couple of years pulled it off).

your way through an issue you’re struggling with. You could sit at a table with any subject expert and jointly create a mind map about their work or field. When I’m working on my own or with one other person a large whiteboard is great, but sheets of 11×17 paper work as well. Use what you’ve got; an artist friend, Betty LaDuke, and I sat in a New York City café late one night and drew out on a napkin the various elements of a giant art project (and over the next couple of years pulled it off).

If you want to move away from paper, you’ll find dozens of mind map programs for your computer.

With group processes use as large a whiteboard in as large a room as you can find, and if it’s day, one with natural light. Open spaces help us open our minds. But flip charts or other large surfaces will work, as well. We mapped out the exhibit design of an entire museum on flip charts. Contributors don’t all have to be in the same room or engaging at the same time. You can crowdsource your mind maps, gathering input from people in your community or around the world. Many online mind map tools, some of them free, make crowdsourcing easy to participate.

How to make a mind map

Mind maps are simple to make. They’re a visual form of the outlining we all learned in school. (The following is adapted from  Tony Buzan but I differ from him on several points.)

Tony Buzan but I differ from him on several points.)

- Start with a central theme or idea. What is mind map going to explore? Write largely (and illustrate) the map’s main subject in the center of the page. The rest of the map radiates from that. While this is the standard way, you can play with it; You can make great maps that don’t just branch from one center. (Click on the map above to embiggen.)

- Each large branch flows out of the center and represents a main idea. From these flow sub-branches (as many levels as make sense). You can draw lines between sub-branches and note what makes them connect.

- Words. Each branch or sub-branch represents one idea. A single word offers more simplicity and power but use phrases as needed; a map on Tolstoy is allowed to say “War and Peace.”

- Use colors to make the map more appealing and help the brain organize different branches/subjects.

- Add images to central idea, your branches and sometimes sub-branches. Don’t worry if they’re not works of art, they aid in creativity and memory.

- Be creative! Break all of the rules and have fun!

Mind maps are not works of art to be framed, they’ll have imperfections. As soon as you finish one you’ll think of some change to make. The first one will be messy. And that may be where you finish. After all, you’re just thinking out loud— rather, visually. The best way to learn to mind map is just begin making them. Play around and enjoy!

Read Mind Mapping, Part 2 HERE!

Top & food mind maps, Tom Peterson

[…] To read Part 1 “Mind Maps: who, what when to use them” click HERE. […]

[…] In a Little Job of Horrors? Try Mind Mapping a New Future. Click HERE. […]

[…] Mind Maps: When, why, how… to use them […]